055. Open Stacks

on the largeness libraries, people who survive by reading, John McGahern, Jeannette Winterson, an Internet Princess, Doodle Dispatches, a new Notebook + SBB is on Facebook now

It seems to me that being the right size for your world—knowing that both you and your world are not by any means fixed dimensions—is a valuable clue to learning how to live.

Jeannette Winterson, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal

So, you’re sitting around in some social setting or another, doing the awkward things you do when you’re trying to conduct ordinary discourse with ordinary humans, when the person you’re talking to drops a clue. Maybe it’s a word choice that is slightly out of place in, say, a dive bar—something like sclerotic or evanescent—not so odd that the person is obviously in the writing trade, but notable. Or maybe they mispronounce a word in the way of people who learned vocabulary from seeing the words, not hearing them, like thinking that you pronounce the ‘c’ in the word indict.

Sometimes it happens when you stumble on something you recognize: as when someone has a mattress, lamp, plant and bookshelf, but no other furniture, or a copy of a certain kind of novel stuck in with some technical manual or history textbook.

The person isn’t ‘passing code’ in the cultural sense, exactly, because it’s not that ostensible. It’s a signal that is somehow both unintentional and unavoidable, a pulse code modulation sent by people who are alive today because at some point in their life they got access to a lot of books, and it gave them a reason to go on existing.

If you meet someone like this and ask them about their upbringing, they will almost always tell you about finding a library.

*

Irish writer John McGahern, one of the great literary lights of the late 20th century, author of The Barracks, Amongst Women and The Dark, is a great example. He had a brutal childhood: a mom who was sick for a long time and then died when he was ten, a dad who was violent, and he lived inside of a closed, provincial culture. In his essay, “The Solitary Reader,” he writes about the first time he encountered a library.

Old Willie Moroney lived with his son, Andy, in their two-storied stone house, which was surrounded by a huge orchard and handsome stone outhouses. . . I was sent to buy apples and somehow fell into a conversation with Willie about books, and was given the run of the library. There was Scott, Dickens, Meredith and Shakespeare, books by Zane Grey and Jeffrey Farnol, and many, many books about the Rocky Mountains. Some person in that nineteenth-century house must have been fascinated by the Rocky Mountains . . .

I didn’t differentiate, I read for nothing but pleasure, the way a boy nowadays might watch endless television dramas. Every week or fortnight, for years, I’d return with five or six books in my oilcloth shopping bag and take five or six away. Nobody gave me direction or advice. There was a tall slender ladder for getting to books on the high shelves. Often, in the incredibly cluttered kitchen, old Willie would ask me about the books over tea and bread.

McGahern is the OG book survivalist. The Dark was censored by the Catholic run Irish state for pornographic content (i.e. literary depictions of consensual sex) and suggestions of sexual abuse by the protagonist’s father. His books were forbidden in Ireland, and he lost his job as a teacher. He could not publish in his own country for a long time, and he went on writing anyway.

A library also figures prominently in English writer Jeannette Winterson’s memoir, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal. She was raised by Pentecostal evangelicals, and her mother was a violent, erratic force, prone to physical and verbal abuse. Winterson, by her own account, fought back:

For most of my life I’ve been a bare-knuckle fighter. The one who wins is the one who hits the hardest. I was beaten as a child and I learned early never to cry. If I was locked out overnight I sat on the doorstep till the milkman came, drank both the pints, left the empty bottles to enrage my mother, and walked to school.

I adore the fierceness of this, but what if that’s all she’d had? An instinct to fight back will keep you alive to fight another day—but what will you be fighting for?

But Winterson also had access to a public library. As she tells it, she started reading the fiction section from A-Z, and it was a good thing that it started with Austen. Later, when her mom was kicking her out of the house, it was a library copy of T.S. Eliot’s “Murder in the Cathedral,” that gave her comfort. She writes,

I had no one to help me, but T.S. Eliot helped me. So when people say that poetry is a luxury, or an option, or for the educated middle classes, or that it shouldn’t be read at school because it is irrelevant…I suspect that the people doing the saying have had things pretty easy. A tough life needs a tough language—and that is what poetry is. That is what literature offers—a language powerful enough to say how it is.

It isn’t a hiding place. It is a finding place.

Imagine being a teenage girl, just figuring out who you love and what are your gifts, being kicked out of your house, living in your car—what if you didn’t have a library to go to?

*

A few weeks ago, this bit about the New York Public Libraries was making its way around the interwebs:

New York's libraries are taking a stand against recent book bans by giving readers across the U.S. access to their e-books for a limited time . . . The "unbanned books" can be browsed, borrowed, and read on any iOS or Android device via SimplyE, the free e-reader app, for those 13 and older. There's a specific "Books For All" collection that has hundreds of out-of-copyright/public domain books available to anyone in the country, with or without a library card. .

This is access to something like 300,000 books. At first blush, it feels like maybe it’s a bigger deal than maybe people realize, assuming that the word gets out and people use the service.

At the same time, it also made me wonder if it’s the access to the content in the books that carries the magic.

Maybe?

I certainly believe in the intrinsic power of stories. And since I don’t know what the brain of a fifteen year old in 2022 is like, I don’t know what kind of impact that unfettered digital access to loads of books would have. I hope it’s big. I hope it’s transformational for a whole lot of young people.

I also wonder if the library itself contains some part of the magic.

There are books organized as digital files, and then there are hundreds and thousands of printed books, collected together into very tall stacks, in a single location that you can go to with your body, that everyone is invited—indeed, encouraged—to use as much as they like, for no cost, and with almost no supervision. All you have to do is promise not to make noise. That’s it.

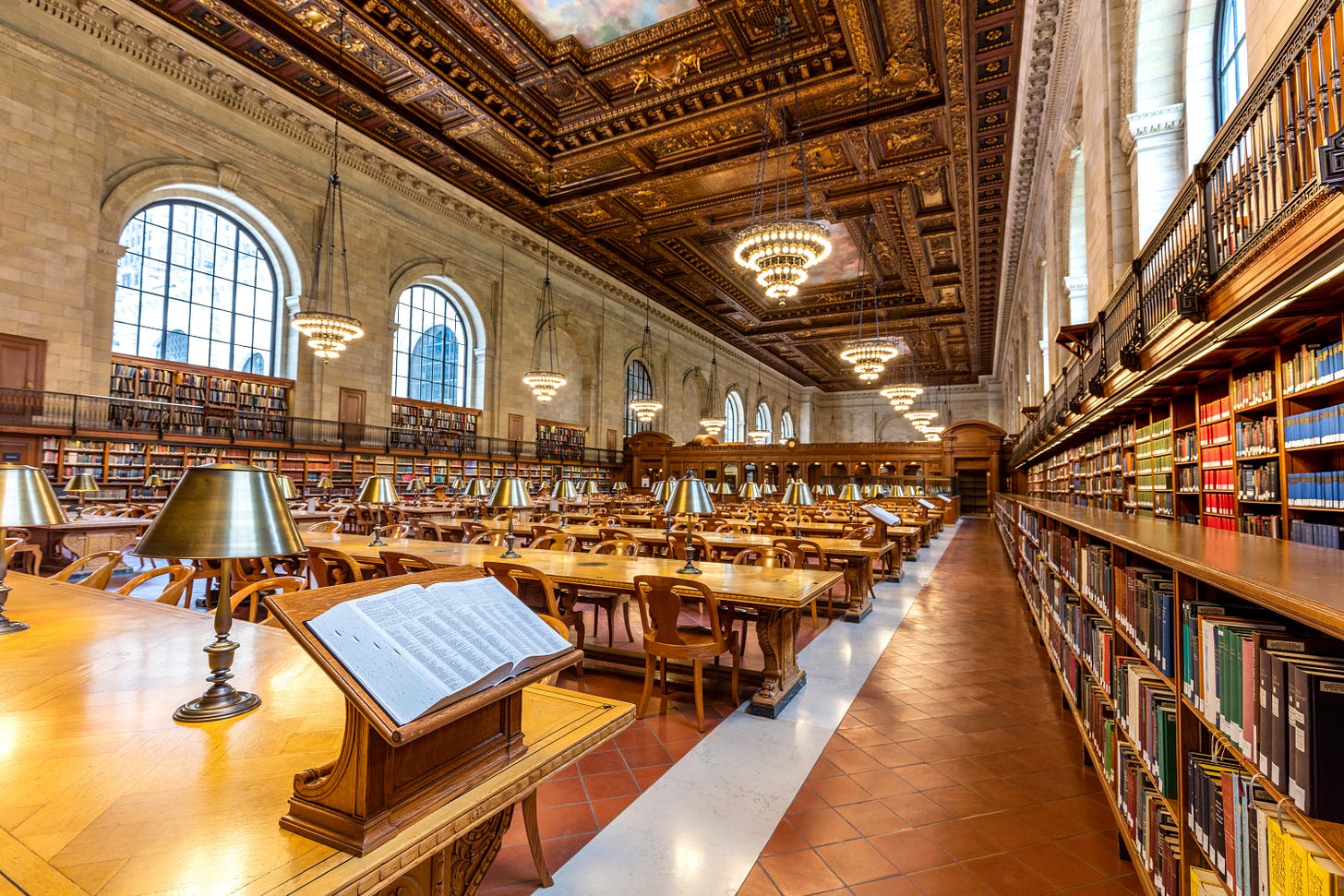

Libraries are definitionally big. Even a very small library has a largeness that comes from the accumulated knowledge contained in even just a couple of hundred books. And, large libraries, as we know, are monuments to architecture and culture. Here, for example is the Rose Reading Room at the New York Public Library, where anyone can go, anytime. I’ve done it lots.

And don’t even get me started on the Reading Room at the British Museum (which is closed now, but has storied history.)

It doesn’t have to be a world class library though. I still vividly remember the Sheridan County Fulmer Library in Wyoming: its particular fluorescent lighting, the many rows of the card catalog with the slips of paper and the little golf pencils (which I thought were ‘book’ pencils until I was at least thirty), the color of the carpeting, the round tables sized for kids, the gnarly polyester squeak of the threadbare bean bags.

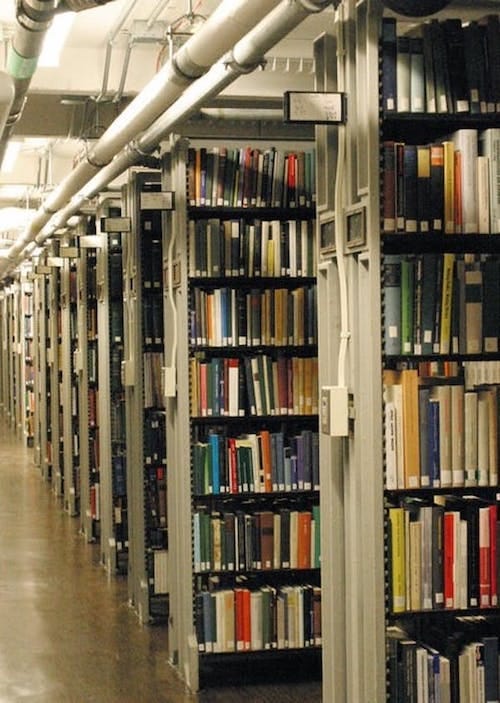

There’s also that word, stack. For the first 45 years of my life a stack meant “a tall series of shelves where books are stored.” More recently, stack means something to do with software, so I looked up its origins. Our friends at Wikipedia tell us that,

the floors of bookstacks did not support the shelving, but rather the reverse, the floors being attached to, and supported by, the shelving framework. Even the load of the building's roof, and of any non-shelving spaces above the stacks (such as offices), may be transmitted to the building's foundation through the shelving system itself. The building's external walls act as an envelope but provide no significant structural support.[4]

Dudes, the book stacks are supporting the whole building, not just housing books. That is some serious largeness.

In McGahern’s description, there is that detail about needing to go up on the ladder to the top shelves—the size of that country house’s library mattered.

If you’re just a kid and your parents are insane or a menace, or aren’t protecting you from someone who is insane or a menace, or you need a place to hide from bullies, or some other misery, or all of the above, you need something that is fucking massive—something so significant and imposing, yet so completely quiet and safe, that you can get lost in it and no one will find you.

That is what a library is.

*

The other thing about libraries is the potential for serendipitous discovery. The internet is infinite, yes, and if a person is well and truly committed to searching online they will be exposed to a hell of a lot of concepts and things. However, for unfettered, unsupervised, bodily exposure to enough information to drown out a religion, a family life, small town mores, and/or whatever else is oppressing you, I am not sure anything else compares to a library.

When I was at college I used to study inside the open stacks. There were dozens of floors, and in busy times, like at the end of term, I had to find a space wherever I could, not just in the PR/PS/PZ section where the English and American literature were shelved. Wherever I was, I always wound up looking at whatever books were nearby. Sometimes it was the color of the binding, or the type of font on the spine, or some other visible pattern that caught my eye. Sometimes I pulled random books off the shelves as a means of procrastination—anything to avoid reading or writing the thing that I was supposed to be reading or writing.

In a library, the great silence and order of the accumulated presence of books is shelter. Yet, you can also hold a book in your hands. What else gives you the aggregate and its parts at the same time. Books will even fall on your head if you un-shelve them clumsily.

Your search in a library isn’t governed by an algorithm and can’t be blocked by a content moderator. The library won’t know or care if you’re browsing for something reactionary. Librarians are there to help you find things, not keep things from you. They aren’t there to sell you anything or harvest your data. They aren’t there to mold your mind. Their whole job is to provide free access to information—all of the information.

The best place to find a banned book is at a library, and yet everyone but the Taliban sees libraries as precious guardians of all that is civil and enlightened. Philanthropists fund them. Parents drop their kids at libraries, unsupervised. No one thinks that we need to limit a kid’s “library time.” No one in Congress is calling for them to be regulated.

There are other ways to free your mind from its constraints: you can drink or do drugs or steal or fight or blow things up—but it’s hard to beat the sweet, safe, brute force of saying fuck you I am going to go read a bunch of books.

No one will say you are stupid if you’re spending all your time at the library. No one will tell you that you should be doing something better with your time.

*

I remember when I first read McGahern’s telling of finding that library. I was in New York City, coping with all kinds of relationship challenges, trying to find a job during the Great Recession, trying (and arguably failing) not to suck as a mom, and trying (and arguably failing) to figure out how to be mentally and physically well even with all of the other things that were going on. I was on the A train on the way home from work wearing headphones that didn’t cancel the noise and breathing through my mouth because that is what you do on the filthy, stinking NYC subway. The other specifics of my misery are blurry, but I was almost certainly standing body to body, packed so tight I didn’t have to hold on to the strap, or stuck inside a stalled train for between twenty minutes to an hour, or next to someone who was sitting in their own urine, or shouting Bible verses, or breakdancing without pants, or all three.

I had read The Dark and The Barracks and had a pretty good idea of the awfulness of McGahern’s upbringing and then there was this story about a kid who is sent to buy apples and encounters the one thing that can set him free.

I remember thinking, oh my god, he’s just like me.

Which, of course, John McGahern is nothing like me and his childhood was nothing like mine, but the recognition that I felt had to do with the dimensionality that Winterson is writing about in the quote at the beginning of this newsletter. Some of us (maybe many of us?) are not born into the world that is the right size for us. We aren’t interested in the profession that our parents want for us, or we don’t like sports, or our skin isn’t the same color as everyone else’s, or we are obsessed with spiders, or poem forms, or blue algae, or whatever it is. We walk around, sending out our existential pulse code modulation, trying to find something that fits—a person, a cohort, a country—that we have only guessed at from reading books.

Sometimes, we get lucky and find a person who recognizes us and we them.

Sometimes, we find a teacher, or a group at school, or a kind neighbor.

Sometimes, we find a library.

Reading Room

You can find more from Doodle Dispatches on Twitter and Instagram. Or check out their witty, carefully curated prints and gifts at DoodleDispatches.com

You Might Also Like:

It turns out that Jeannette Winterson is on Substack.

Internet Princess is an extremely interesting blog by “writer, cultural critic, short-form video essayist, full-time performance artist, and medium-insane woman,” Rayne Fisher-Quann. I like it for its risible mix of feminisms, GenZ syntax, excellent wordsmithery (e.g. “lobotomy bait” and “dissociative pout”) and self-acceptance.

What I'm Reading

The first few chapters of Brian Rutenberg’s Clear Seeing Place wrecked me this week, in the good way. It’s about painting, but it will resonate for anyone who is a maker: writer, poet, musician, coder, builder—it’s a book about seeing things and bringing them into being.

Rutenberg describes art as an invitation to “come closer, let’s twist nervous systems around one another and construct a place that wasn’t there before.” [ 🙌🏻 ]

Help SBB Grow

Survival by Book is now on Facebook! In addition to reading SBB via email, the Substack app, Substack reader, or on courtneycook.substack.com, you can also now access new issues from FB. Importantly, you can also share and comment about Survival by Book there, which will help expand our readership.

Survival by Book now has a Notebook. It’s a new section that is opt-in, not opt-out, which means it won’t be emailed to you unless you tick the box for it in your Substack settings. (Reach out if you don’t know how to do this, happy to help.) If you don’t tick the box, you will still see it in the Substack app and reader, and you can always just navigate to it by going to courtneycook.substack.com/s/notebook

If you made it this far, you are a magnificent reader and true fan. You should definitely become a paid subscriber!

Become a paid subscriber | Get a t-shirt | Find us on Twitter and Facebook

I loved this, Courtney. I felt a pinch of sadness when I read that no one is trying to regulate libraries. Maybe not, but in some communities the libraries are closing, shrinking, and/or being turned over to third-party operators. We fought a proposal to do this a few years back and had a HUGE Fight to build and support the city’s new central library. So far, the library is with us.

I’m one of those kids who felt the world drop away the minute I walked into a library - any size, any place -- and just breathed in the possibilities. I loved the privacy and you are right -- no one ever told me to spend less time in the library. It was my happy place.