061: Who's in Charge of Our Cities?

on geospatial data & the case for human-sized tech + Jo Petroni inspires, Doodle Dispatches has a birthday, Aella lights up a new thought galaxy, & Gabrielle Zevin keeps me up all night

When I arrived in Amsterdam last week, the first thing that struck me is that people seemed really happy in a way that seemed like a long-lost memory.

I wanted to draw conclusions about how this is because of cobblestones and good bread and not having a million guns lying around and stuff, but I think that it was mainly because a heat wave had just passed, so everyone was happily not sweltering. Although, there is a way in which the sight of two humans, sitting side by side at a bistro table, looking out on a canal, each with a drink in hand, on a Saturday afternoon, seems rare in the U.S., maybe because we have busy, multiple lane roads bisecting our cities instead of canals?

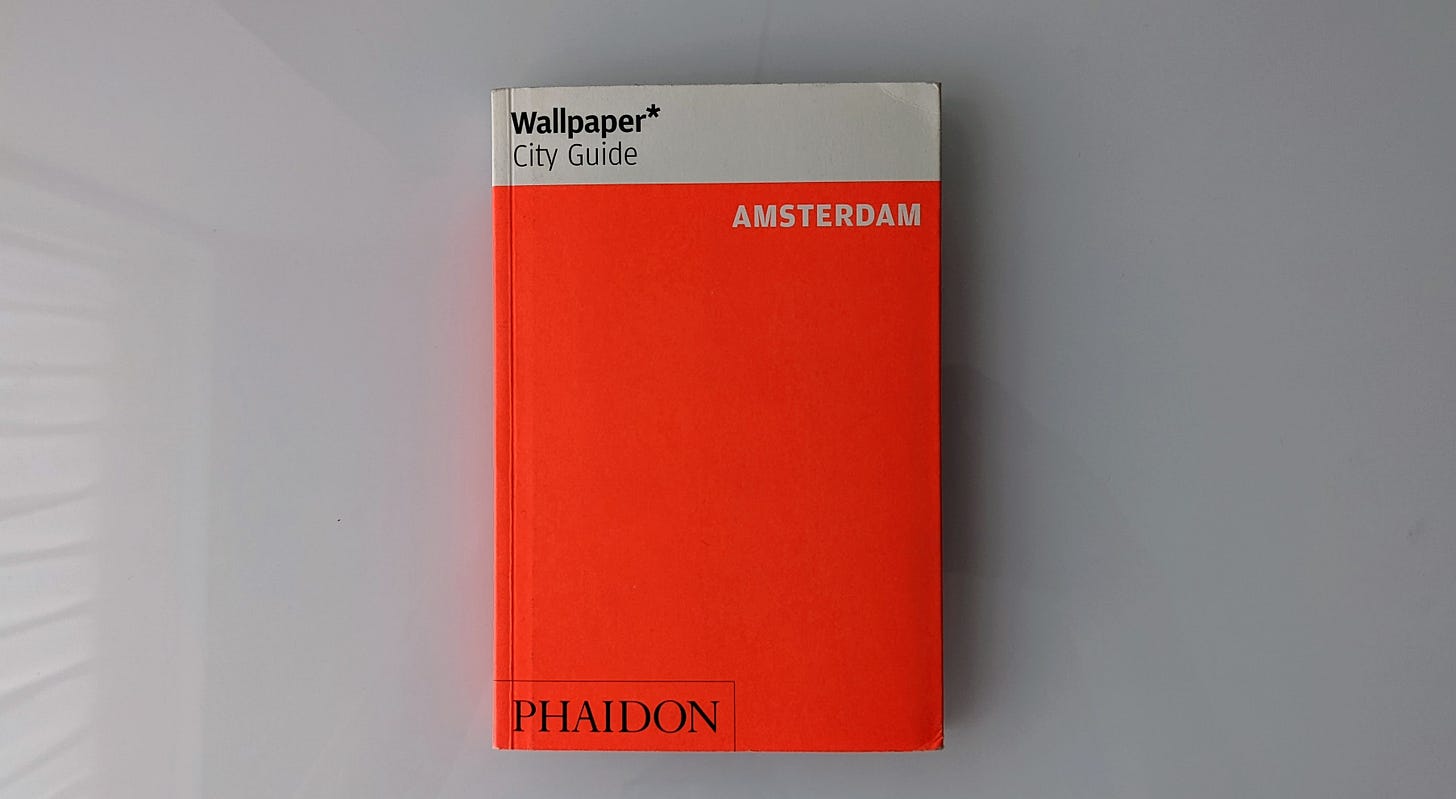

I’m here for work, but I got here a couple of days early which gave me a chance to do some sightseeing, helpfully curated by this book:

and its map: