070: generations of men with tobacco in their beards squinting at the bridges of Königsberg

isomorphisms, rhodonea curves, rhetorical logic, and the writings of Elif Batuman

It is an inherent property of intelligence that it can jump out of the task which it is performing, and survey what it has done; it is always looking for, and often finding, patterns. - - Douglas R. Hofstadter

I have a craving for mathematics right now.

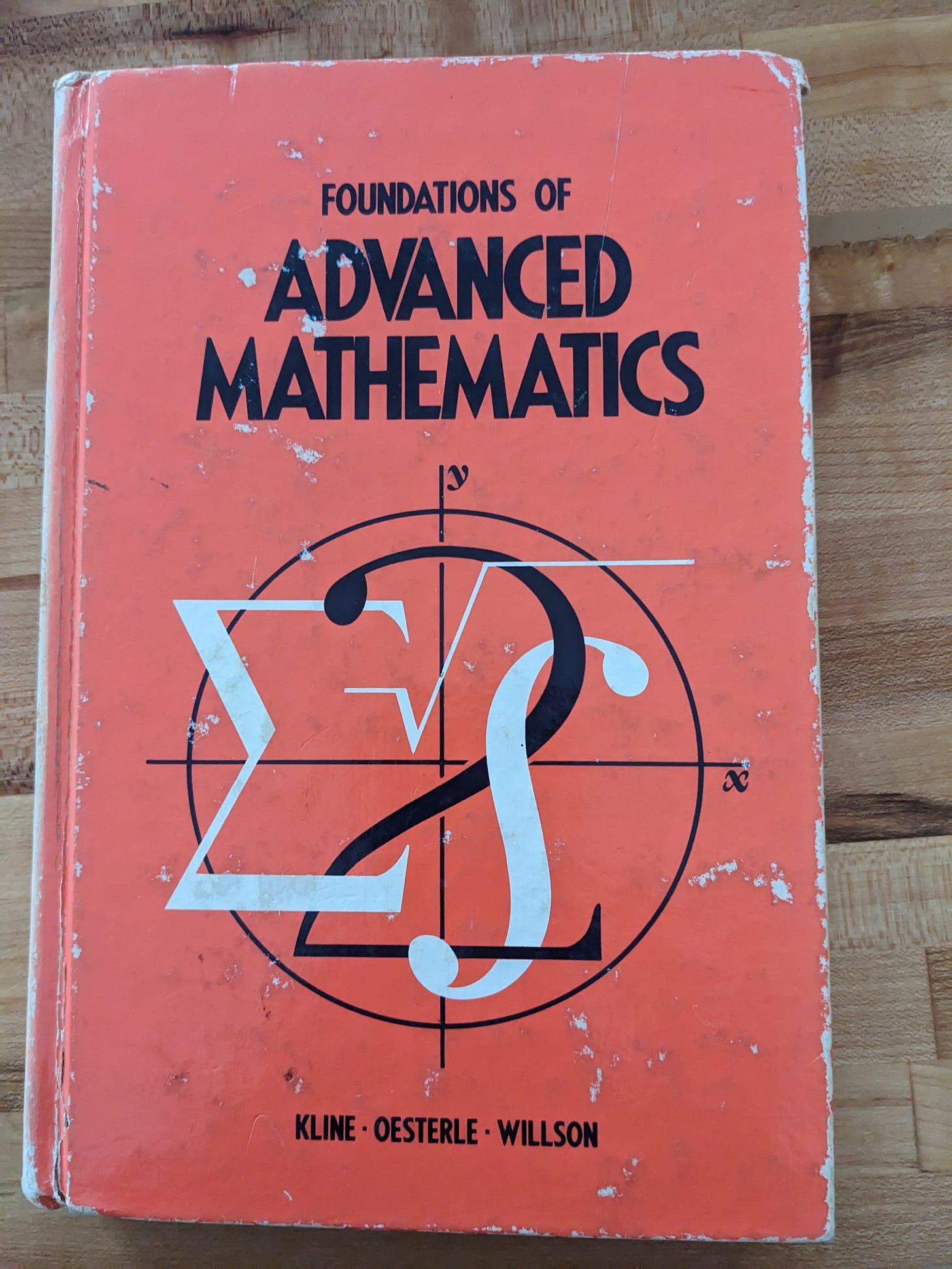

I am winter starved for a conversation resting on tenets older than the last meme cycle or one person’s lived experience. I crave the clarity of thinking based on systems and axioms tested by successive generations of men with tobacco in their beards who squinted in sputtering candlelight while checking and double checking whether it was possible to cross all the bridges of Königsberg once and only once.

I don’t have time to care that they were all old white dudes. I don’t have time to care that their privilege was not uniformly distributed. I can’t fix the past. I can plumb the knowledge of the past to fix the present.

I want to stand on their vitamin-deficient, probably misogynist, blessed, cursed shoulders, pouring over my trigonometry textbook, thinking about how to build a much better future.

Hofstadter again: it seems that if we want to be able to communicate at all, we have to adopt some common base, and it pretty well has to include logic.

It has taken me a long time to realize that conforming to the logical precepts of mathematics doesn’t mean being boxed in. It just means that the center does hold and maybe things won’t fall apart. The more I read about formal mathematics, the more I see how tensile it is.

Algebraic topologies are especially stretchy. According to Wolfram, they are “the mathematical study of the properties that are preserved through deformations, twistings, and stretchings of objects . . .tearing is not allowed.” I.e. they are the yoga pants of mathematical forms, supportive enough to hold you in, but with lycra so you can bend.

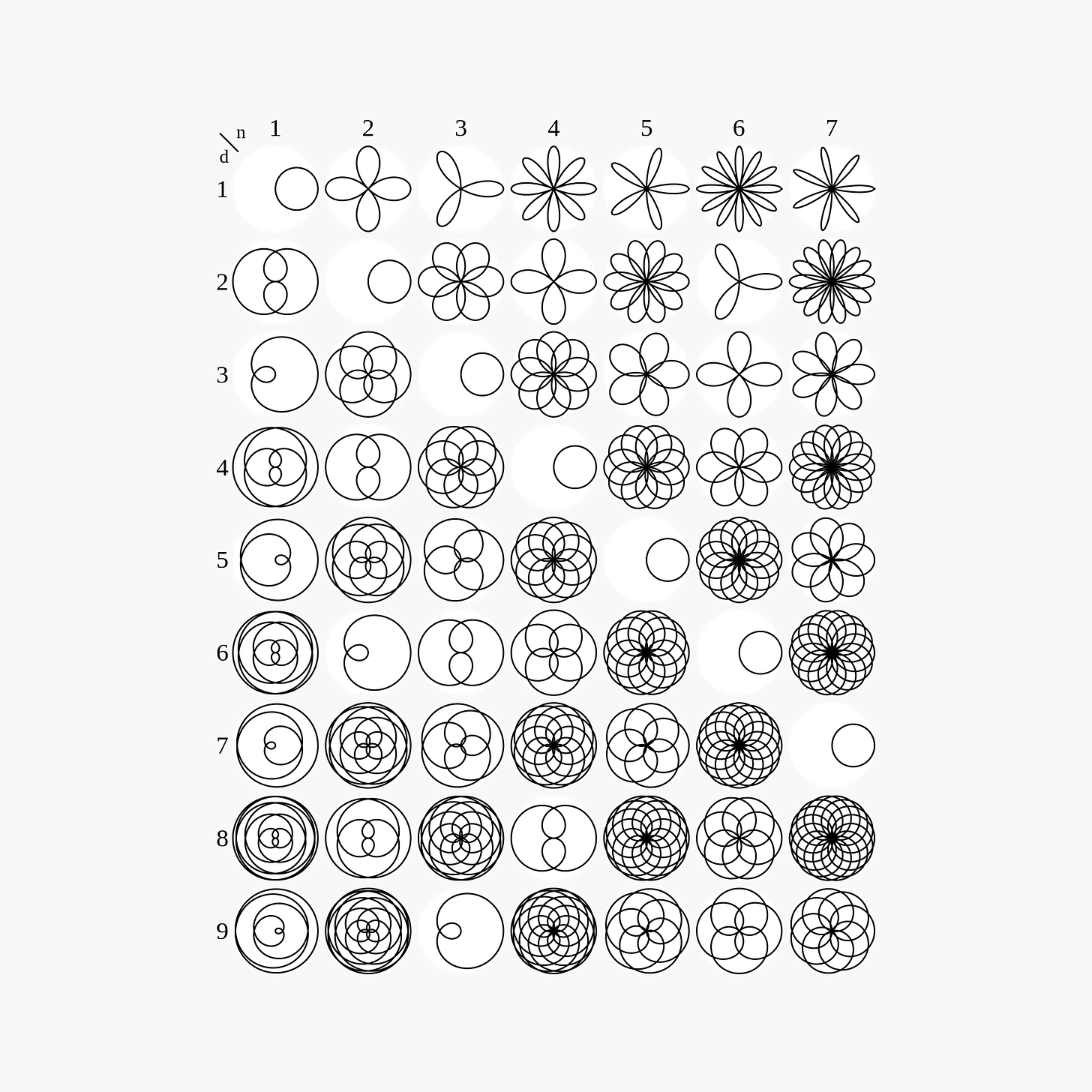

A very pretty topology is a rhodonea or “rose” curve. Here’s a bunch of them.

The ‘petal’ shapes of the rhodonea curves are the result of bits and pieces of Algebra and something called a “polar equation” which makes me think of the descriptions of the great and noble Iorek Byrnison, the magnificent panserbjørne, or armored bear, in Philip Pullman’s The Golden Compass, which is not isomorphic to this diagram.

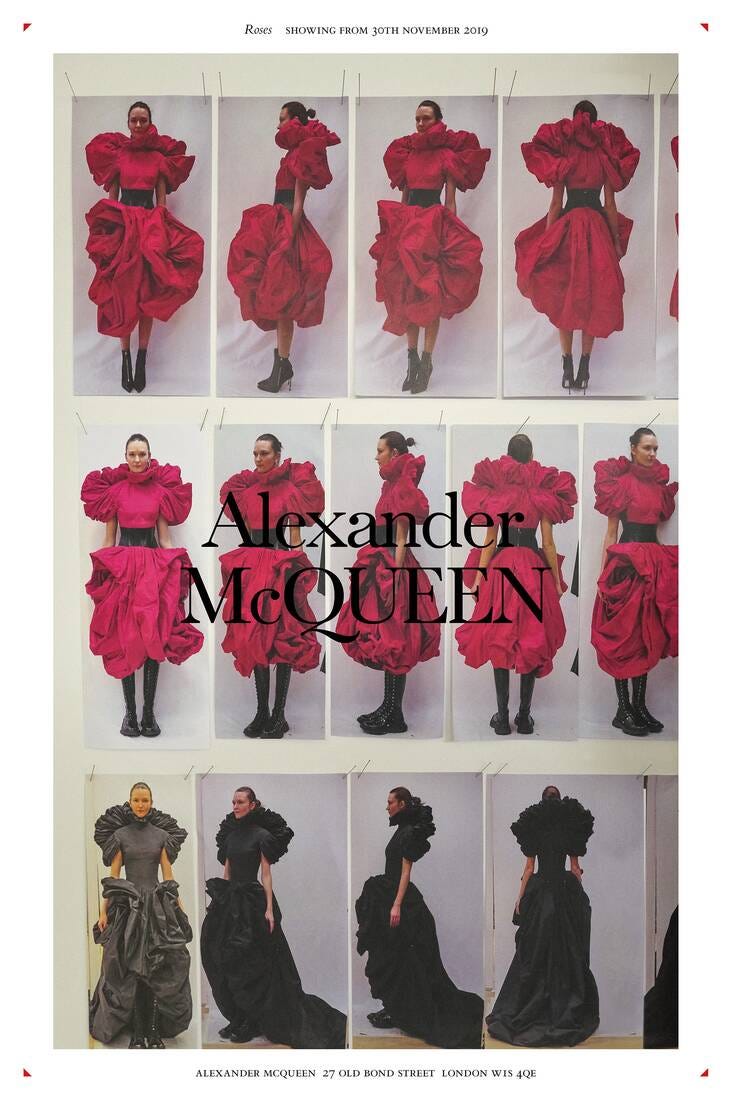

This broadside from the Alexander McQueen “Roses” show is though:

This is why Sarah Burton is, and Alexander McQueen was, more than just a fashion designer. The aesthetic is grounded in a mathematical system, referencing and repeating variations on circles, polygons, and curves, following some rules and breaking others depending on the structural integrity of the garment, in the service of creating something that is beautiful.

Imagine what the field of mathematics would have looked like if those old bearded dudes had ever encountered a woman.

∞

Here’s another isomorphism: Relationships—especially intimate ones—can function like topologies.

The way that the characters of Selin and Ivan relate to each other in The Idiot by

is a great example. The shape of their interaction continuously twists and curves to account for space, time, and the vicissitudes of being college students in the late 90s.They begin in the shape of two students in a Russian class, practicing a dialog. Then, their connection morphs into the shape of a new technology called email:

I pressed C to start a new message and then, just to see what happened, I typed “Varga” into the recipient box. Magically, the email address appeared, and the full name: “Ivan Varga.” That was Ivan. I thought a moment and started to type.

In this digital plane, they have the freedom to bend into more private shapes, to speak in stories and codes, feeling their way into what is the right form.

Ivan recognizes more quickly that email isn’t a complete system, writing to Selin that “my love for you is for the person writing the letters.” Sometimes their shape stretches between Berkeley and Harvard, the contours of its lines discoverable only when Selin uses the “finger” command to learn where and when Ivan is logged in. Later, they meet and re-form into two people who are on a college campus. Still later, they re-form as two people who are in Hungary.

In one scene they are together next to an emergency door on an airplane. Ivan is sitting on a part of the floor that says “DO NOT SIT HERE.” Selin is leaning against a wall that says “DO NOT LEAN.” They tell each other jokes about scientists and Hungarian farmers. As is so often the case, Selin doesn’t say most of what she is thinking.

Ivan, Ivan. He got up in the morning, put on some clothes he got from somewhere, drank his orange juice and went out into the world of chalkboards and motorcycles. He could be really arrogant sometimes. His jeans were always too short, and he thought clowns had something complicated to teach us about human fallibility. And still no waking moment went by that I didn’t think of him. . . Every sound, every syllable that reached me, I wanted to filter through his consciousness, At a word from him I would have followed him anywhere, right off the so-called Prudential Tower.

To me, the elasticity of their connection lets them be about as intimate as two people who are just getting to know each other can get, while protecting them from illogical norms and customs that have nothing to do with who they are and what they want. They don’t have to spray paint the body shape of their “identities” on to a sidewalk and then go about subjecting each other to forensic evidence.

They follow some of the rules of dating and break others, depending on the structural requirements of their time and space continuum, creating something that is beautiful.

∞

Which brings me back to the genesis of my craving for mathematics: my frustration with the continuously flattened, unsatisfying, two-dimensional quality of the current discourse.

Reviews have been replaced with hot takes, it would seem, which is why the critical response to The Idiot and its sequel Either/Or seem, well, rhetorically infantile. To adjudicate, in a review, on whether or not Ivan is exploiting Selin by being vague about his relationship status, is to rob the book of one of the central, literary tensions. The ambiguity of their dynamic is the point; they are both trying to figure things out in the halting, agonizingly vulnerable, quite beautiful way that relationship dynamics should be figured out.

Other reviewers disliked how the sexual tension between two, nerdy young people who live in their heads stays on a long slow simmer. The objection in this case, I guess, is that the pacing doesn’t conform to the storyline of a limited Netflix series.

Batuman’s novel is dryly witty, dense with literature, linguistic, and mathematical references, and fearlessly honest about the awkwardness of dating and sex, and yet our country’s leading book reviewers can’t step outside a subjective system of reflexive assumptions promulgated by Instagram commenters.

Which is why I dug up my high school Algebra II textbook and started thinking about the writings of dead white male mathematicians.

Previously in Topologies:

I love Elif, though I've only read her nonfiction, not her fiction. Sounds like I have a treat in store!

“The poverty of the current discourse”—so wonderfully put and so true. Today I read about 15 opinion pieces and a dozen book reviews. This is my first meaningful read of the day. Yes, fuck the rules made and adjudicated by Instagram commenters.