077: On Writing Letters

a letter to a soldier, Nina Stibbe's "Love, Nina," chat groups as an epistolary form, letters as evidence of human connection + links to Charlie Porter's new book and Tom Stevenson's war reporting

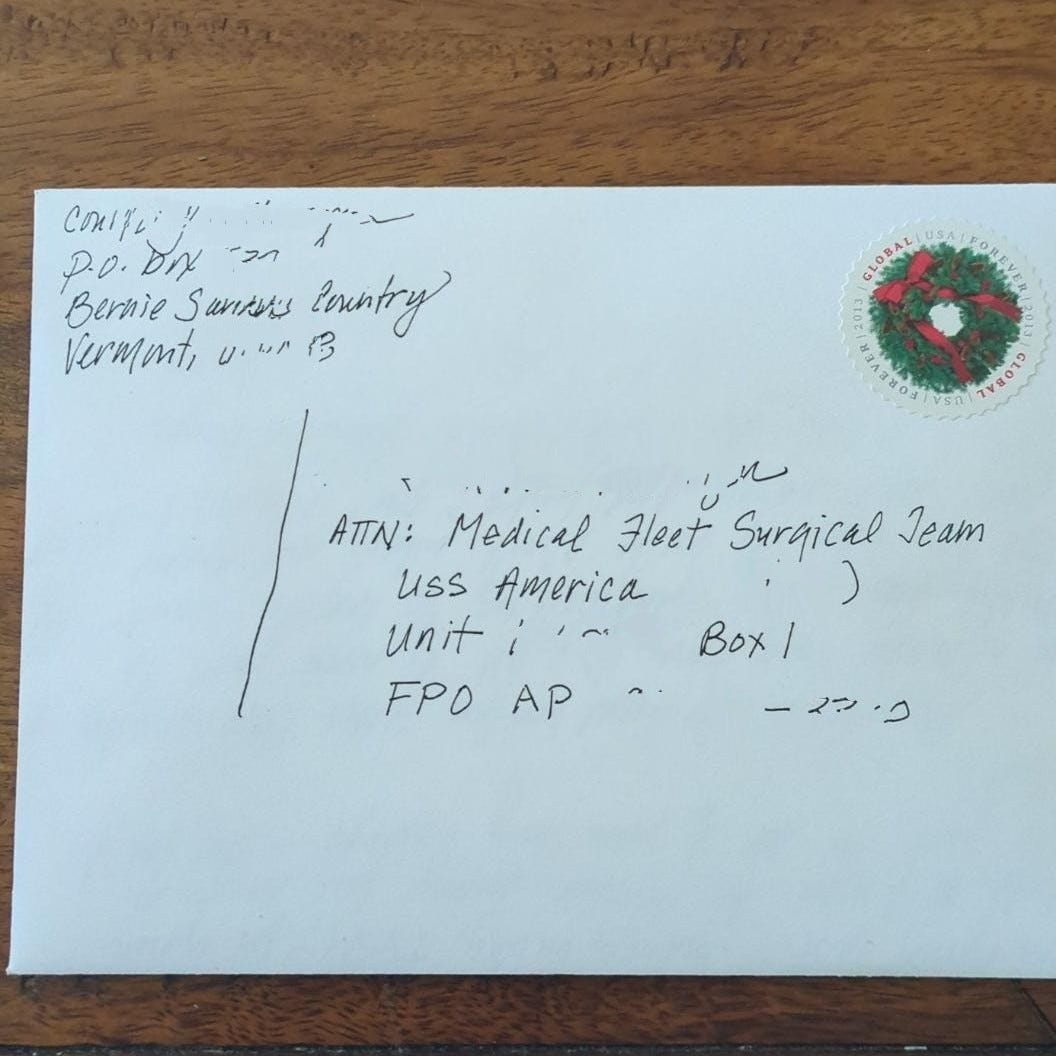

I wrote my son a hand-written letter this week. Not a note stuck on top of a package. Not a typed, printed letter. A real letter, hand-written on thick paper, that I folded up, put into an envelope, and affixed with a Christmas-themed forever stamp that I found at the bottom of a drawer.

I wrote to him because he’s on a US Navy amphibious assault ship somewhere in the South Pacific and it’s the only way I can reach out to him. He’ll be underway for between eight weeks to three or four months. We didn’t know exactly when he was going to leave until the morning he left. We don’t know what the ship’s mission is or where they are going.

I asked, “can you at least tell me if you’re going near Yemen? “

“Mom. I’m in the Pacific Fleet.”

His birthday is coming up. When he turned 18 at boarding school, I had this idea of getting his dorm advisor to order pizza for the whole dorm. Thank God I asked him first. He was adamantly opposed.

This year’s birthday is a million years later, but once again, he’s in a dormitory- like situation. I can’t call or video or send food. I thought about sending a flash drive of movies, since they can’t stream or download media, but I’m not sure if the Fleet Post Office (FPO) would deliver a random flashdrive to a service member who is underway. In fact, let us hope that they would not. I could send a box of cookies, but I don’t know how long it will take to get there. It needed to be special in some small way, so not a card. Cards are so impersonal. So, a hand-written letter.

I ended up having to do two drafts, because the first one revealed to me that I had forgotten how to write a letter. I started to tell a funny story about his grandparents, but about a page in, I realized it was going to take three pages to write out the kind of thing that is now conveyed in a single screenshot with an emoji. It’s not like I could delete and start over. In the old days I would have chucked it in the trash. This one got shredded for compost.

By the second draft I had some muscle memory back, though my handwriting has gone to sh*t. I wrote a couple of short, cheery anecdotes and added birthday well-wishes—maybe 200 words.

What I really wanted to write was something like I adore you and I’m so glad you were born, please be safe and come home soon about 200 times.

It was barely two short pages, but I still got a cramp in my writing hand.

*

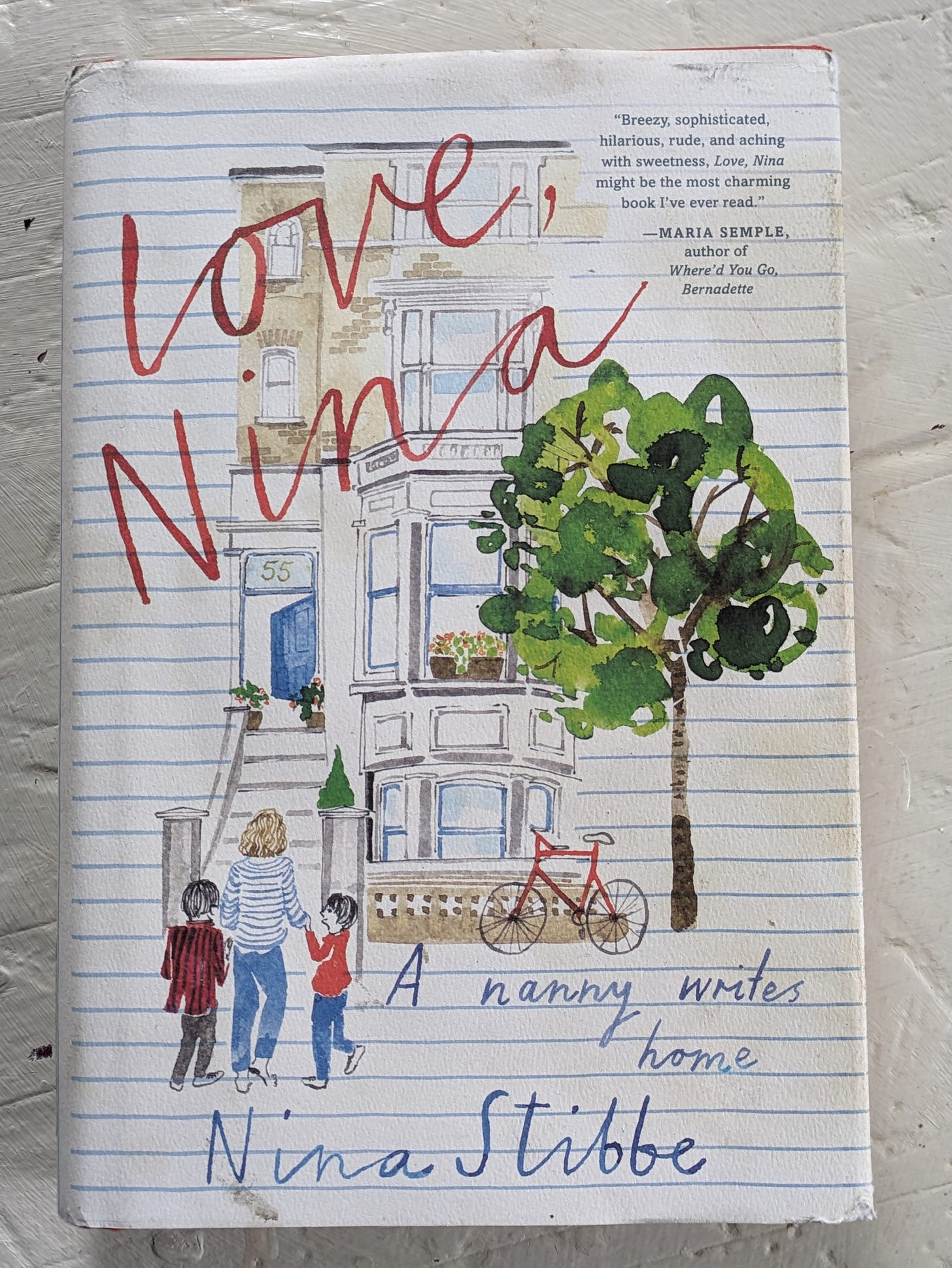

Last week, I also read British writer Nina Stibbe’s first book, Love, Nina, a collection of letters that Stibbe wrote to her sister while working as a nanny in the Primrose Hill neighborhood of London in the early 80s. Her unwitting subjects were Mary-Kay Wilmers (editor of the London Review of Books), Wilmers’ two school-age sons, and a group of unusually literary neighbors, including writer and playwright Alan Bennett and novelist Deborah Moggach.

What makes the book great isn’t its literary subjects, it’s Nina’s savage sense of humor. Her dispatches about her charges—Will and Sam—and the adults who orbit them are full of irreverent descriptions and bits of comical dialog, the sharp edges of which are softened by her affection for the family and their friends.

I remember writing letters like the ones in this book. Reams of paper filled with hilariously uninformed observations about what we now call “adulting:” what adults say to each other when not talking to children, what things cost, how to cook, what advice the police will give you when your lace underwear are stolen off of the clothesline that was strung too close to the road. There’s no drama to speak of, there’s just a young person observing everything that is going on around her with humor and an open mind.

The best part are the dialogs, like this one with Will and Sam:

S&W talking about whether or not they're going to take up smoking.

Will: I'm going to have one after every meal.

Sam: So four per day, then?

Will: Three.

Sam: It's unhealthy.

Will: Yes, especially if you've got asthma.

Sam: I'm going to smoke one per day walking to the tube.

Will: What about walking back from the tube?

Sam: Two per day, then.

Will: What about after every meal?

Sam: Stop encouraging me, I'm just having one per day.

As I was reading, I noticed how these bits of repartee reminded me of a couple of my chat groups. It’s interesting that we still have a form that captures excerpts from the clever (silly, weird, stupid, sweet) things that people say, thirty years after these letters were written.

*

It’s hard to break the habit of posting in the chat group I have with my son and daughter, even though I know he can’t see the texts right now.

Sometimes I post things anyway. I notice my daughter doing the same thing. We’re not texting the usual number of memes, links, and photos of 1990s era Toyota Forerunners—I don’t think either of us wants him to get off the ship to 327 unread texts. But it’s as though some things won’t have the same kind of meaning if my daughter and I just texted them to each other.

What makes epistolary writing so appealing is that the audience is known. It makes it intimate—there’s a you that the writer is writing to. It creates a kind of trust. If you’re writing something to someone, and it’s not via your lawyer, it’s because you like them and they like you. The guard comes down. You can take off your mask. You have shared context, so (most of the time) the subtext is clear. You can use shorthand to make a point and make jokes that no one else would get. The person you’re writing to already knows what you mean.

When we get to look over the shoulder of someone writing a letter, whether it’s the real Nina Stibbe or Ta-Nehisi Coates writing to his son, or Samuel Pepys writing for all of England, or the fictional Bridget Jones or Adrian Mole writing to the most awkward among us, we feel share in the intimacy. It’s reassuring to remember that other people have the same worries and desires. Other people get jealous, or feel mischievous at the wrong time, or hide food in a napkin under the table. Other people say appalling things to their children and are only half joking.

Letters show who we are when we aren’t performing.

*

When I was in high school, my friends and I used to pass notes to each other at school. One or two, maybe more pages, written on lined notebook paper and folded into tiny squares that we passed in the halls. For some unknown reason this was considered reprehensible—there were plenty of teachers who would confiscate the notes and give you a detention for writing them. We wrote about how boring our teachers were and how we were going to kick Cheyenne East’s butt at the football game on Friday and whether or not we should go to SuperAmerica to get cheeseburgers for lunch. We quoted song lyrics, endlessly. Once, a guy I liked copied out every single verse of The Cure, “Why Can’t I be You” into a note written to me on yellow lined legal paper. I still feel kind of swoony when I hear that song.

In his allegory of the cave, Plato differentiates between the true form (Platonic ideal) of an object that exists in the real, sunlit world, and the shadow form that is reflected on the walls of the caves in which we dwell. The former, he says is something we understand with reason and the latter is something we understand with our senses. I don’t think he’s making a judgement that one is better than another, though maybe he is—I have never really comprehended this allegory in the way that I probably should. But I like the idea of that there might be exponential numbers of shadow forms that are reflecting a small group of fundamentally real things.

It makes a kind of lazy, intuitive sense that there are only a few, tangible objects that resonate over the course of human existence and that everything else is a variation on those forms. Some examples: a record is a shadow version of people playing music in a room, which is a shadow version of people playing music around a campfire. Fonts are a shadow version of letter presses, which are shadow versions of glyphs, inscribed on papyrus, which are shadow versions of cave markings. A wiki is a shadow version of an encyclopedia which is a shadow version of a library.

I think that chat groups are the shadow form of the notes that we passed in high school and that those notes are themselves the shadow version of the real, sunlit thing: the pristine happiness of riding around in a Ford Bronco with five or six of your best friends listening to Guns N’ Roses, “Paradise City,” saying all the things you absolutely couldn’t say in front of your parents and teachers. (I don’t know why the apostrophe is after the N, don’t @ me.)

I still have some of those notes. I didn’t just imagine that there were people I loved with whom I could talk about the Utmost Importance of Bono all the way to the state wrestling tournament in Casper. I have evidence, discernible by all reasonable persons, that I can hold in my hands

My chat group with my son and daughter is the shadow form of the three of us lying around on my couches watching youtube videos, which is itself the shadow form of being tucked up in bed with them when they were children, reading stories, which itself is something like the shadow form of what it was like when I could hold them close in my arms. The texts remind me that our connection with each other exists even when one of them is Philadelphia, or in Okinawa, Japan, or at an unknown location in the South Pacific and the other one is at an unfamiliar location in Uzbekistan, or Berlin, Germany, or Ann Arbor, Michigan.

I hadn’t realized how important my chat groups had become to me, until I sat down and tried to write a letter.

*

In the box where I keep all my most precious hand-written letters, there is a little book that I made during the few, agonizingly years when I had to live apart from my daughter. It’s a “back and forth book” that is a mix of letters and diary notes. There aren’t that many entries in it, but it’s still important to me because of the few, incredibly adorable things that my then 11-year old girl wrote in it.

In the same box, I have many dozens of letters written back and forth between my children’s father and their dad from when he was in the Army. They date back from when he was at Advance camp before we were married and continue through Armor Officer’s Basic Course, Ranger School and a myriad of other military trainings. Among them are the have the letter from when he and his platoon discovered a cache of arms in Somalia. I also have letters from the year when he was deployed to Korea. In those days we could talk, at most, once or twice a month on a landline and it cost a fortune.

I have my letters from those years, too, ones that were written to my children’s father and others that I wrote to my parents and friends. Here are the letters about how our toddler son liked to vogue with my roommates when I was still at college and the one about how he chose a picture of a gigantic pig lying on a bed of candy to be the picture that identified his cubby at pre-school. Here is a letter about my daughter’s first bites of solid food and the one about how I put a fan in front of the refrigerator and aimed it at her baby carrier to keep her cool on the day when the three of us had to move into a fourth floor apartment during a heat wave.

I still have letters from my friend who died in a car accident. I still trace his handwriting sometimes.

I have letters from later years, when my children’s father was in Iraq, incredibly sad ones that are painful to read, but that I would never give up because they remind me of the love and intimacy that we had even when we were breaking up, because they stand against the flattening of memory.

I wonder if we’ll someday all forget that group chats are the shadow form of time that we spend together. I wonder if we’ll forget why we have vinyl records and print white borders around our digital photographs. Right now, most of us still remember listening to a record all the way through or printing photographs in a chemical bath in a darkroom, but for how long?

I haven’t figured out what TikTok is the shadow form for. Do you know?

*

I do have an email for my son right now. It’s not only for emergencies, but it’s not something I would use to send a meme about Taylor Swift at the Superbowl. Last last week, he used it to send us a single photo from the ship. No caption. No other information.

It’s a snapshot of three people in motion. A person lying on a hospital bed, abdomen bared, another person, seen from the back, who is holding an ultrasound wand to the solder’s belly, and my son, facing the camera, standing next to the ultrasound machine, with his hand raised and seemingly in the middle of saying something.

In my daughter’s and my chat, we worked together to interpret the photograph:

Why is the soldier smiling? What are those baklava things they are wearing? what is the ultrasound being used for?

My only guess is that the baklava things act essentially like fancy reusable hair nets. Maybe it was an appendix issue or something?

Interesting. They look warm though?

Hm you think it's a temperature thing?

That doesn't make sense because they’re indoors though

Maybe it's like the x-ray bibs at the dentist. They have crazy gloves on too

oh you're right! I didn't see that

now I can see they are wearing scrubs or somesuch too. So that must all be their surgical gear. At first I interpreted it as cold weather gear and that they had just come inside.

Well they aren't in the main operating room. So it must be a pre-exam room. I interpret the main operating room as through the door. Like the label is on the outside not the inside, but it could be either.

I like it that the photo is a puzzle.

It's fun bc you have all these skills for reading photography but then when it is actually a totally new context for you it is meaningless

He looks so tall!

I don’t yet know any of the actual answers to any of these questions.

I could ask his girlfriend who knows more about what his life as a Navy surgeon is like, or I could ask his dad who knows more about what life on deployment is like, but I don’t think I will.

I don’t want to ask someone else. I want to ask him for the answers when he’s back on dry land—whenever that is.

I want to ask him in whatever is the non-amphibious-assault-ship, peacetime, shadow form of the connection I feel when he’s with his girlfriend in my kitchen, with my daughter and some friends, and we’re cooking something, and he’s telling a story and getting mad because he’s getting interrupted, and everyone is hungry and happy and chaotic.

I want to ask him when love and family are what is real, when the world’s weapons and wars are the shadow form of a now-forgotten memory of something that doesn’t ever happen anymore.

Recommended Reading

Love, Nina by Nina Stibbe \ Guardian Review \ a Substack review on

Went to London, Took the Dog, by Nina Stibbe \ TLS Review \ Buy it at Blackwell’s

Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion, Charlie Porter \ “Bloomsbury Chic” in the New Yorker \ review in Wallpaper \ Buy it at Blackwell’s

“Rubble from Bone” in London Review of Books \ the most reporterly, plainly delivered, report I’ve read about the bombardment of Gaza, to date.

Beautiful. I loved passing notes in high school.

The mom-longing that runs through this piece seems so loud to my sensitized ears—the letting go we are always meant to be practicing, but will never master. I’ll be thinking of shadow forms a lot this week.